Circuit breaker is about slow response

In his seminal book Release It! Michael Nygard elicited the “Circuit Breaker” pattern. He documented the pattern as one of the fundamental stability pattern. However he did not give any implementation schematic and also the documentation does not go in depth about the logic and fundamental need for this pattern. As mentioned in the book, circuit breaker pattern is for preventing cascading failures, unbalanced capacities, slow responses. But most often, it is coupled only with timeout tracking. In his blog about Circuit Breaker Martin Fowler also referred this pattern only for tracking failures. I think using circuit breakers only in case of failures is inappropriate at least from a logical perspective if not implementation perspective.

Response time and timeout

In some sense, timeout can be viewed a type of erroneous response. With this view point, timeout is a case of extremely slow response. It is the upper bound on response time from a service. Circuit breakers which track timeout errors will be unable to guard against a service returning responses with latency close to timeout value. The effect of an extremely slow response from a remote service or a timeout error is increase in number of concurrent active requests in the system . This behavior can be explained easily with Little’s law. More over using Little’s law for this analysis provides insights into need for circuit breaker.

Little’s Law and its repercussion

In queuing theory any resource be it human or machine is considered a service center. Hence it is an excellent tool to model users of application, application and hardware in combination.

Littles law is presented as:

N = X * R

where

N = Number of users in the system typically known as concurrency

X = Throughput – Number of completed discreet events per unit time

R = Response time – Time taken for completion of discreet event under observation

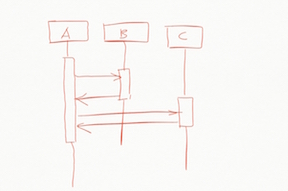

The law can be explained further in relation to figure below.

Here, client invokes B and C which are remote services.

Let For service B, response time be B1

Let For service C, response time be C1

Now the overall response time for A = Processing time at A + B1 + C1

So, by Little’s law NA = ( Processing time at A + B1 + C1 ) * XA

Hence NA ∝ B1 as well as NA ∝ C1

As apparent from derivation above, concurrency at A depends directly on response time of B as well as C. This understanding helps in making informed decisions as explained in next section.

Design considerations

Generally service response timeout value is set at much higher level than average response time value; typically 4 to 10 times. The range is necessary to allow for random case of slow response. However in case of continuous timeout responses or successful responses with near timeout value from remote service would result in 4 to 10 times increase in active requests at client. Circuit breakers help alleviate this problem by setting a average latency threshold value per given time. The average latency threshold value is closer to normal latency value than time out value.

The choice of threshold value force developers to make choices about latency behavior of a remote call which otherwise would have been missed. The threshold value is a range between expected latency from remote call and timeout value. Fixing a certain value on range requires a conversation with provider of the remote service about expected latency behavior. Also since one would not want to trip circuit breaker on a single timeout response, one has to make decision of percentile value and corresponding response time i.e. 90th percentile with 1 sec latency. I think this a great desirable side effect of incorporating circuit breaker.

In conclusion, circuit breaker is a great pattern to build robust applications and a must in micro services paradigm. It makes latency behavior explicit in code.

PS: On a side note, non blocking calls make this entire discussion irrelevant as concurrency at A solely depends on its own processing time.